My Romanian friends ask: So what did you do all month in Albania?

The Albanian Sneeze

I arrived at the Nënë Tereza International Airport late at night, following a transfer in Munich. No direct plane routes exist between Bucharest and Tirana: to fly south, you need to first head thousands of miles north. After two take-offs and landings, my flight-induced anxiety left its mark, and I was completely worn out. I felt halfway across the globe, even though a mere 900 kilometers separate Romania and Albania. Apart from knowledge of the recent past – that Romania and Albania were close as a result of shared communist experiences – I knew nothing about Albania. The only other fact was that a forefather of mine, Aromanian and the first Dedu in the family, left Albania for Romania at the end of the 18th century. As soon as the plane’s wheels hit the tarmac, all my anxiety disappeared, and a profound sentiment of home washed over me. I still try to make sense of it now.

I first became acquainted with Albanians at the Munich airport. There, I observed that every man over sixty wore a mechanical wristwatch, the kind that seemed to be passed down through generations. It soon became clear that time operates differently in Albania. It’s a sort of “traditional” time, less fragmented than the digits shown on our electronic devices yet more rigorous. In Romania, mechanical wristwatches are on the verge of extinction. During the month I spent adapting to Albania’s classical flow of time, I rediscovered my childhood summers. Under pleasant skies without a drop of rain or trace of clouds, I spent endless days. Under scorching heat, often as high as 40 degrees, the sole form of structure came in hours set aside for lunch, naps, and sleep.

Nowhere have I ever had as much time at my disposal than in Albania. In Tirana, I knew nighttime was upon us when the elderly filled park benches around the fountain of the Colosseo Hotel. Nearby, children splashed themselves with water where the embassy street began. Closed off to the public, the embassies seemed distant. Bored guards would stand in front of each grand enclosure dedicated to Western, Eastern, or other faraway lands. Each building appeared closed in on itself, in a manner that inspired seriousness. While countries like Germany and France would greet each other from behind diplomatic windows, an accompanying frenzy of clinking wine glasses could be heard from the open-balcony receptions across the street.

Nowhere have I ever had as much time at my disposal than in Albania. In Tirana, I knew nighttime was upon us when the elderly filled park benches around the fountain of the Colosseo Hotel. Nearby, children splashed themselves with water where the embassy street began. Closed off to the public, the embassies seemed distant. Bored guards would stand in front of each grand enclosure dedicated to Western, Eastern, or other faraway lands. Each building appeared closed in on itself, in a manner that inspired seriousness. While countries like Germany and France would greet each other from behind diplomatic windows, an accompanying frenzy of clinking wine glasses could be heard from the open-balcony receptions across the street.

I knew nighttime was upon us when the woman who sold roasted corn appeared on my street. On Rruga e Durrësit, she would set up her small, carbon grill and settle into a fisherman’s chair. Surrounded by large bags, she would await her customers. Each night, a pleasant breeze rolled in from the sea. At the Hemingway bar, old black and white films were projected onto the decaying wall of a neighboring building. In the heart of the city, thirty story buildings made of concrete and glass were being erected around Skanderbeg Square, an enormous pedestrian space. In Tirana, everything undergoes destruction before meriting construction.

Mornings began only once locals met up at the terrace cafés for their daily coffee. Coffee, often paired with a complimentary chilled glass of water, is never taken at home in Albania. The tradition was perhaps inspired by the Italian model. Along the course of forty years, Italy was, in fact, the country for which Albanians longed most. A free country, just across the water, yet inaccessible. Romania, on the other hand, was surrounded by communist nations. There were no nearby Western neighbors nor safe havens towards which to run. Where could one go – to communist Hungary? To the Serbs? Despite the illusion of freedom – that a boat was all one needed to cross the Adriatic and reach cities like Bari – Albania was one of the most highly guarded states of the communist bloc. Nobody left, and nobody entered. Westerners who passed through the country first went to the salon to ensure their appearance did not provoke any unwanted attention. Enver Hoxha, prime minister at the time, filled the country with over 150,000 bunkers to “protect” his population against a capitalist invasion – something both impossible and improbable. It was pure propaganda. In Tirana, two such bunkers were transformed into museums, memorials dedicated to the victims of communism. I never imagined a place could emotionally affect me as much as the Sighet Memorial of the Victims of Communism and of the Resistance in Romania. I never imagined a dictator as incompetent as Ceaușescu could govern elsewhere. That is, until I came across Bunk’Art 2. Among families of French, Italian, and Nordic tourists, I visited the memorial. The adults educated themselves, superficially, about communism while they strolled from one room to another. Their children ran through the colorful chambers void of fresh air and natural light while I worked to hide my tears. To them, the bunker was a theme park. How can someone understand something they’ve never lived through? What reference points can they have if they come from the independent land overseas? I left dumbfounded.

In Tirana, lunchtime arrived when the excessive heat drove everybody off the streets and into the air-conditioned indoors. Precisely during those moments, I would walk for kilometers on end in the shade. Unlike in Bucharest, each boulevard was lined with trees. I would walk past corner shops located in the basements of buildings, where I could buy anything from phone chargers to imported Italian dresses. Only while on route to the park with an artificial lake did I feel the heat begin to let up. I would sit on a bench and listen to the people around me, particularly drawn by the sound of men sneezing. From day one, the Albanian sneeze surprised me – it was like a friendly greeting that could be heard all the way to Durrës, forty kilometers away on the shoreline. What struck me most was how similar this sneeze was to my father’s. Ever since I was young, my mother would tell him: “Anton, stop sneezing so loudly! Be decent and use a handkerchief!” To me, the Albanian sneeze was the clearest sign that I had reached the land of my ancestors.

On that first night of my arrival, Tirana was still an unknown city for which I had few expectations. I imagined it to be a different type of Bucharest. At three in the morning, I couldn’t sleep and ended up smoking on the balcony of my apartment. How interesting. I thought about the plane ride between puffs. All the men over sixty wore mechanical wristwatches.

In Tirana, lunchtime arrived when the excessive heat drove everybody off the streets and into the air-conditioned indoors. Precisely during those moments, I would walk for kilometers on end in the shade. Unlike in Bucharest, each boulevard was lined with trees. I would walk past corner shops located in the basements of buildings, where I could buy anything from phone chargers to imported Italian dresses. Only while on route to the park with an artificial lake did I feel the heat begin to let up. I would sit on a bench and listen to the people around me, particularly drawn by the sound of men sneezing. From day one, the Albanian sneeze surprised me – it was like a friendly greeting that could be heard all the way to Durrës, forty kilometers away on the shoreline. What struck me most was how similar this sneeze was to my father’s. Ever since I was young, my mother would tell him: “Anton, stop sneezing so loudly! Be decent and use a handkerchief!” To me, the Albanian sneeze was the clearest sign that I had reached the land of my ancestors.

On that first night of my arrival, Tirana was still an unknown city for which I had few expectations. I imagined it to be a different type of Bucharest. At three in the morning, I couldn’t sleep and ended up smoking on the balcony of my apartment. How interesting. I thought about the plane ride between puffs. All the men over sixty wore mechanical wristwatches.

Terra incognita

In life, we experience a number of events that are predestined yet deemed mere coincidences. These moments pass us by, never to occur again. During the lockdown, while the world came to a standstill, I would order myself food and think about the Balkan vacation I had planned pre-pandemic. I longed not for Paris or Rome, but for Sarajevo and Belgrade. For the Bulgarian side of the Black Sea. I imagined what it would be like to live in Montenegro or in Albania for some time. After I became disenchanted with the West, I fell passionately for the Balkans. I strove to understand the region’s complex history alongside its magnetic allure. As Romania’s neighbors from across the hills, their histories intertwine with ours.

It was then that I began writing a book on Aledonia, an imaginary country that shared much of its culture, including its traumas and collective mindsets, with the Balkan nations. Throughout the pandemic, I explored Aledonia’s modest lands. The stories I wrote somehow captured the overwhelming sentiment of home I felt while in the Balkans. Only when the government loosened restrictions and once more permitted travel did I stop my writing: my literary game had lost its purpose.

By the time I found out I was going to Albania with a TRADUKI residency, I had almost forgotten about Aledonia. In Albania, I discovered a capital city like the one in my book: located at a short distance from the sea and near a mountain whose peak could be reached via gondola. In my book, Aledonia’s landscape was predominantly hilly and covered with lakes full of fish found in no other parts of the world. On my travels, I trekked across Albanian plateaus in dated minibuses and ate lunches on the shores of the Belsh lakes. I never did, however, get around to tasting the rare fish found only in Lake Ohrid. In my book, I named the Aledonian currency “aleki.” In Albania, I easily navigated my way using the “lek.” In my fictional story, Ernest Hemingway owned a vacation home in which he wrote his final book, never to be published. In Tirana, I came across the Hemingway bar, which embodied something of the writer’s spirit despite him not having anything to do with Eastern Europe. My imaginary nation wasn’t a member of the European Union and underwent a hundred-day communist rule in the 80s that forever changed the mentality of its citizens. Regardless of how short-lived, I realized, a totalitarian regime leaves its mark.

Mere coincidences! You might say. You’ve heard all this before – your mind’s playing tricks on you! Sure, but it’s no coincidence that the Albanian language, of which I understood nothing, seemed so familiar that it could have been a language I had spoken in another life. Or in a dream. The absolute serenity that washed over me during my entire stay was again no coincidence. This wasn’t my first trip – it was a return. I had already visited Albania before I could remember.

Hemingway Bar

Hemingway Bar

By the time I found out I was going to Albania with a TRADUKI residency, I had almost forgotten about Aledonia. In Albania, I discovered a capital city like the one in my book: located at a short distance from the sea and near a mountain whose peak could be reached via gondola. In my book, Aledonia’s landscape was predominantly hilly and covered with lakes full of fish found in no other parts of the world. On my travels, I trekked across Albanian plateaus in dated minibuses and ate lunches on the shores of the Belsh lakes. I never did, however, get around to tasting the rare fish found only in Lake Ohrid. In my book, I named the Aledonian currency “aleki.” In Albania, I easily navigated my way using the “lek.” In my fictional story, Ernest Hemingway owned a vacation home in which he wrote his final book, never to be published. In Tirana, I came across the Hemingway bar, which embodied something of the writer’s spirit despite him not having anything to do with Eastern Europe. My imaginary nation wasn’t a member of the European Union and underwent a hundred-day communist rule in the 80s that forever changed the mentality of its citizens. Regardless of how short-lived, I realized, a totalitarian regime leaves its mark.

Mere coincidences! You might say. You’ve heard all this before – your mind’s playing tricks on you! Sure, but it’s no coincidence that the Albanian language, of which I understood nothing, seemed so familiar that it could have been a language I had spoken in another life. Or in a dream. The absolute serenity that washed over me during my entire stay was again no coincidence. This wasn’t my first trip – it was a return. I had already visited Albania before I could remember.

On the road

At the edge of town lies an enormous bus station that reminds me of the smaller Militari or Filaret terminals in Bucharest. The space is crowded with minibuses and coaches. The ones in the best conditions head for the coast, towards tourist destinations like Durrës or Sarandë. The clunkers, on the other hand, struggle to start and are filled to the brim with locals bound for obscure cities and villages. There is no air conditioning on these buses. Albania does not have a properly functioning railway system. Without a car, the only way to explore other parts of the country is through local transport. Rooted in the past, you know when these buses will leave, but never when they’ll arrive.

In the waning hours of morning, the heat is already unbearable. Representatives from each company call out their destinations like a promise, inviting and directing their customers towards parked cars which will only leave once all seats are occupied. The bus drivers hover in the shade, near the baggage compartments. Unaffected by the chaos around them, they either nod off or snack on something. Most of my inner-country journeys began at this station. Over time, I learned it was crucial to bring along patience, water, and at least one cheese byrek. I’ve traveled in contorted positions where my arms or legs would fall asleep while I kept my eyes fixed on the window, looking out towards Durrës, Krujë, Gjirokastër or Sarandë. Or towards Elbasan and Korçë if I left from the terminal on the opposite side of town.

Anyone and everyone would make use of the buses. In fact, no journey would be complete without some foreign tourists scattered among the locals. These travelers, usually solo backpackers, seemed doomed to aimlessly wander from one place to another. In their minds, however, they had precise goals and destinations: two days in Albania, another two in Montenegro, and a final stop in Dubrovnik before hopping onto a flight home. When my sandals fell apart near the end of my travels on the white, pebble streets of Gjirokastër, some backpackers accepted me as their own. A Swedish man with whom I had previously exchanged a few words in Sarandë admired my compact backpack: You travel light!

While discovering Albania through its network of roads, I wondered how my forefather, the first Dedu, made the 900-kilometer journey between Albania and Romania. During a period in which the infrastructure was far worse than it is now, how many days would it have taken? Which routes would he have used? What inns would he have visited? Although I continued to know nothing about him, I felt like I was walking in his footsteps the entire time. Despite the two centuries and entire generations of relatives that separated us, I felt him beside me each step of the way.

On another trip, an Albanian man transported long, wooden planks from Tirana all the way to the other side of the country. To make room for them, a few seats were disassembled and then restored to their positions. Somehow, everything fit. Eager to construct his home, the man happily removed his planks and left when we reached his mountain village. While still in the mountains, the minibus broke down. We stopped in front of a holy spring for what I imagined would be a brief water break. Once I saw the driver carry jugs full of liquid towards the overheating radiator, I realized this wasn’t the case. Along the route, any additional passenger we picked up was offered a folding fisherman’s chair that could be mounted in the aisles between seats. Nobody was left behind. After exiting the mountains on route to Korçë, the vast waters of Lake Ohrid materialized before my eyes. An elderly couple sitting next to me regarded me with a childlike joy: Don’t we have a beautiful country? Their eyes conveyed what words couldn’t express. I had tried to converse with them earlier before realizing we shared no mutual language. The wife fell asleep with her head against her husband’s shoulder. A warm sensation of peace filled my soul.

Aromanians

As the story goes, the first Dedu came to Romania from Albania at the end of the 18th century. During the rule of Grigore Ghica, he arrived as an Aromanian political refugee. One of his descendants, either a son or nephew named Dimitirei Diamandi Dedu, owned all the buildings and lands surrounding the Șerban Vodă Bridge. He even owned an inn in Bucharest. People referred to his properties as “Dedu’s homes.” Although Dedu lived a decent life, things fell apart after he befriended and loaned money to the Greek Negroponte. Shortly after, the Greek disappeared, taking a large portion of Dedu’s fortune with him. From that point on, the family history became complicated – estates were gained and lost, sometimes even gambled away. My aunt Greta became Queen Marie of Romania’s lady-in-waiting. My aunt Meme left for Paris. And so on… Eventually, communism found my relatives already in poverty and nostalgic for the golden days. The only things I inherited from them were pieces of the fragmented past.

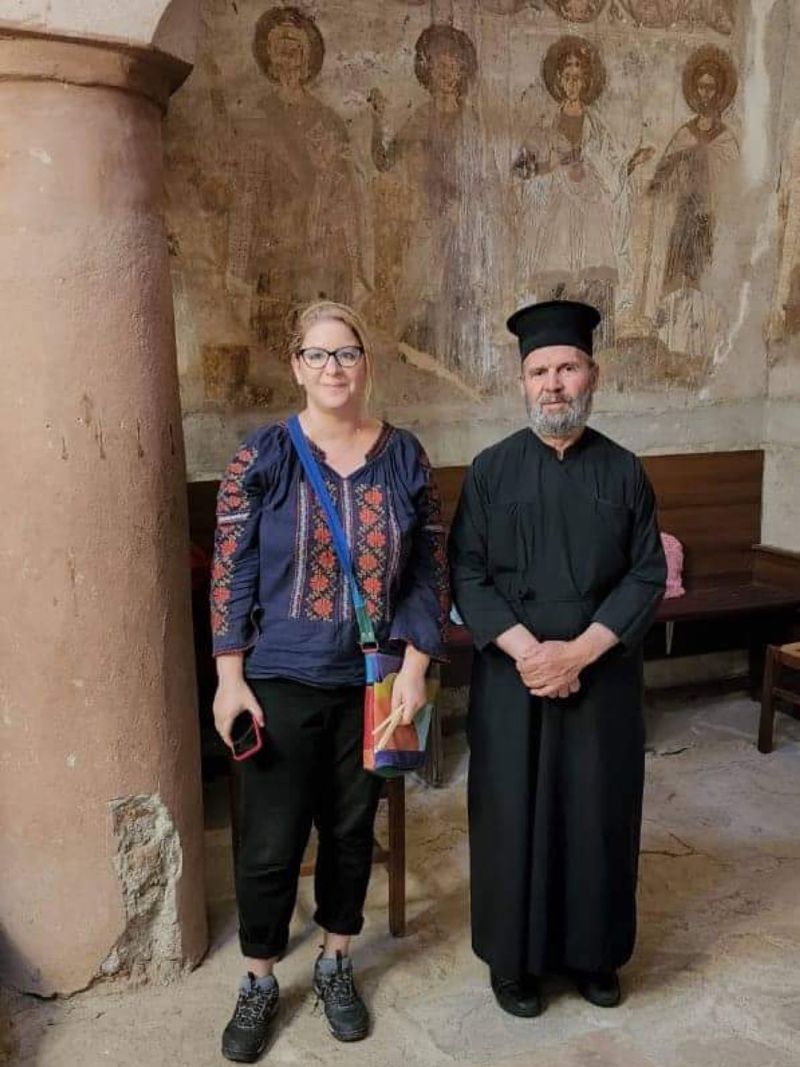

While in Albania, I encountered several Aromanian communities in Tirana, Mekat (the village near Vlore), and Korçë. My travels even symbolically ended in the long-lost Aromanian city of Moscopole (Voskopojë). There’s this feeling that Aromanians are everywhere, scattered across every corner of the country. On the street, you’ll often learn that the grandmother or grandfather of a stranger you meet is Aromanian. Even the Albanian dialect of the Aromanian language caught me by surprise – it seemed like an ancient variety of Romanian! It was exactly how I imagined we would be speaking if the Romanian language developed in a linguistically isolated place, like on an island in the middle of the sea, void of evolution or external influences. The sentiment of home I felt in Albania became so accentuated that I didn’t want to leave. I felt as if I were already back in Romania, although in a better version characterized by honesty and an absolute sense of camaraderie.

At the end of my travels, I returned home without an inherited, mechanical wristwatch. Time once again became fragmented, divided into inconsistent shards in which I could no longer find myself. I returned to my book on Aledonia, longing for Albania with each passing day. I no longer believe in coincidences, and I know that some things in life truly are predestined.

Excerpt 1

In search of Dede Gjon

Legend has it that my ancestor, Dede Gjon, was an extraordinarily wealthy man in Aledonia. He was so wealthy, in fact, that he would mint coins with his face on them at whim. The simple addition of his features was often enough to increase the value of a coin. At that time, even though Aledonia belonged to other countries and empires, as history often goes, a Dede coin was important enough to get you a loaf of bread, a barrel of wine, an overnight stay at a decent inn, and a woman. Sometimes, you could even purchase a castle depending on the mood of who you found yourself negotiating with.

Legend also has it that Dede Gjon was a shipping mogul during his youth. He traveled the world and buried chests of his fortune everywhere. Always on the run, Dede never had a chance to return and retrieve his treasures. He was constantly prosecuted and persecuted by his enemies, as any affluent man of our times. When he could no longer remain in Aledonia, his wanderings led him to the principalities across the Danube in what is now Romania. According to the stories, he would have had enough money to purchase an entire country with his hidden wealth. Had he desired, Dede likely would have gone after Muntenia or Moldova. With his influence, he could have obtained them both. He couldn’t have, however, acquired Transylvania – forces beyond his control were at play there.

When I was young, I was heavily invested in Dede Gjon’s travels. “What happened to Dede’s money?” I would ask my father, Anton. “Who knows,” he would shrug. “Thieves probably robbed him along the way. He wouldn’t have been able to carry much anyways. After all, it’s only a legend.”

As a child, my family lived in a two-bedroom apartment on Calea Moșilor. During winters, the radiators stayed cold to the touch and the electricity shut off at night. In the small room, we would wrap ourselves in woolen clothes and huddle under thick blankets to conserve heat. The Bucharest of that time was a black hole in a galaxy unbeknownst to the world. Since we couldn’t even turn on the radio and listen to the stories of Mateiaș Gîscarul for the hundredth time, my father resorted to telling us stories about our incredibly rich forefather who came from a far-off land called Aledonia. What interested me most about these tales were the feasts my ancestor would hold.

“Would he eat chicken?” I asked my father.

“Of course, he would have roast chicken with every meal.”

“And grilled pork chops?”

“Pork chops? He must have eaten entire chunks of meat right off the bone!”

“Would he drink Pepsi?” I added.

“Pepsi wasn’t around two hundred years ago, Adina. Let’s think reasonably.”

Excerpt 2

The balcony

The Aledonian poet gave me another reason for why the Melody Hotel was an excellent choice. Namely, for the balcony in my apartment.

He told me I was lucky – the Melody Hotel, constructed during the interwar years in a neo-Aledonian style with art nouveau influences, was one of the few remaining buildings with open balconies. More precisely, my hotel room extended outwards through means of a small platform that was enclosed by a weak, ornamental balustrade. I couldn’t step on the balcony unless I was fully dressed – people could see me from every angle. While I looked down at the world, the world looked up at me. It felt as though I was leaving the apartment without actually leaving the apartment.

An open balcony, the poet continued, represented the decision of the tenant to see and to be seen. Almost all the balconies of the city, he lamented, were enclosed. Like small cuckoo bumps growing out of someone’s head. The people living inside wished neither to see nor to be seen. What an interesting theory, I thought. Later, I remembered that most of the balconies in Bucharest are also enclosed. Even the insignificant extensions on the standard, communist buildings that tenants could only use to dry their laundry. People closed off their balconies for various reasons, whether to obtain an ounce of privacy or to gain additional living space. Ironically, the newly-built concrete buildings have no balconies attached to them, only enormous windows.

“Why do you think people no longer want to see or be seen?” I asked the poet.

“It’s unclear,” he replied, preoccupied. “For us, the desire began at the end of the hundred days. Once the communist regime fell, Aledonians wanted to close off their balconies – they felt safer that way.” He paused, then added: “But you should be proud of your open balcony… It’s a privilege to have!”

During the period in which I lived at the Melody Hotel, I followed the poet’s advice. I stepped out onto the balcony at least once a day, primarily to smoke since it was prohibited indoors. Otherwise, I would peer down at the patrons drinking their morning coffee on the hotel’s street terrace. Some appeared to be decent, notable people. Others seemed like good for nothings without better ways to spend their time or money.

Eventually, the carriage drivers appeared in front of the hotel’s fountain. They stopped to give their animals water, although this was explicitly forbidden. Even foreigners could understand the sign depicting an animal that was neither horse nor donkey slashed through with a red line.

Every evening, the elderly locals who could not afford to take their coffee at the Melody Hotel’s terrace would sit around the small fountain. On benches, they would chatter away in Aledonian. Sometimes, the lavish waiters from the hotel would shoo the elderly away, confusing them for beggars. The hotel’s terrace spilled out into the street, blurring any clear delineation between the rich and the poor. You never knew on which side of the line you were while there.

During my stay, I also came to know the woman who sold corn on the street. She would arrange and prepare her station near the fountain every night, first taking out her small, carbon grill and then several cobs of corn. Surrounded by large bags, she would set to work. The smell of roasted corn would travel all the way up to my balcony, driving me insane. Everybody would buy her corn, whether they came from the street terrace or open space beyond.

Long after the terrace had closed and the carriage drivers left, I would see a woman walk her child in a stroller. She often came in the middle of the night from the nearby Embassy Park, making a slow turn around the fountain before exiting from where she entered. She probably needed to feel the calming silence and safety of the night. Inside her stroller was a statue-like child with unblinking eyes that stared out at the stars. I wondered about what crossed the child’s mind, and whether the walk even mattered to the young one. The mother fulfilled her duties regardless and took her child outside every single night.

English translation of the essay and excerpts by Andreea Ciobanu.

Adina Popescu, born in Bucharest, Romania, in 1978, has a BA in Film Directing. She has been working as a cultural journalist for Dilema veche magazine since she was 18 years old and is now its senior editor. For her work she has received several prestigious accolades. In addition, Popescu is a documentary filmmaker and author. Her first children's book was published in 1999. Since then, several books for children and adults have followed. The book Bukarest–Berlin, ohne Rückkehr? oder: Wieso sind die Rumänen nicht wie die Deutschen?, written together with author Jan Cornelius, came out in 2021.

Photos by © Adina Popescu

Project Manager: Barbara Anderlič

Design: Beri

English translation of the essay and excerpts by Andreea Ciobanu.

Adina Popescu, born in Bucharest, Romania, in 1978, has a BA in Film Directing. She has been working as a cultural journalist for Dilema veche magazine since she was 18 years old and is now its senior editor. For her work she has received several prestigious accolades. In addition, Popescu is a documentary filmmaker and author. Her first children's book was published in 1999. Since then, several books for children and adults have followed. The book Bukarest–Berlin, ohne Rückkehr? oder: Wieso sind die Rumänen nicht wie die Deutschen?, written together with author Jan Cornelius, came out in 2021.

Photos by © Adina Popescu

Project Manager: Barbara Anderlič

Design: Beri